Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

State, national rankings vary widely on Arizona students’ performance

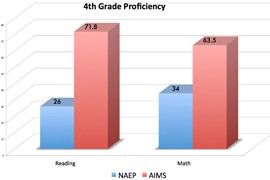

WASHINGTON – Arizona school officials boasted that nearly 72 percent of state fourth-graders scored “proficient” or above on a state reading assessment in 2010. A year later, a national assessment put the number of proficient fourth-grade readers at just 26 percent.

So do Arizona administrators have a math problem or a reading problem?

Neither, it turns out.

Though Arizona’s proficiency numbers differed significantly from those in the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the state was not alone. Only two states, Massachusetts and Louisiana, reported state scores anywhere near the levels of proficiency on the national test.

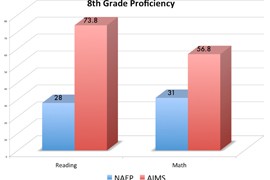

That’s because the state and national tests often test in a different way. While it may not be an apples-to-oranges comparison – one Arizona educator said it’s more like “red apples to green apples” – state officials said having the two tests is a valuable tool for helping schools figure out how they’re doing.

“The numbers are very different, and it certainly means we have work to do,” said Joe Thomas, the vice president of the Arizona Education Association.

Both the state and national tests rank students on one of three levels: basic, proficient or advanced. But standards for each level can vary widely state to state and state to nation, said Arnold Goldstein, a director at the National Center for Education Statistics.

“Proficiency on state tests may mean the minimum for grade-level performance, or it could be a higher standard, all the state standards differ,” Goldstein said. “That’s one of the messages from the report.”

The report, released last month, is the NAEP, which showed the Arizona numbers from 2010 and the national numbers from a year later. In addition to the gap in fourth-grade scores, it reported a similar gap in eighth-grade reading proficiency between Arizona and the nation, with the state reporting 73.8 percent proficiency and the national test ranking 28 percent proficient.

Goldstein said the national test policies are determined by a committee of subject matter experts, educators and field specialists.

“The committee goes through student responses to these questions and they decide what level of performance represents basic work, proficient work or advanced work,” he said.

The nationwide scoring, which samples students from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, allows Arizona to compare itself with other states, as well as comparing its own year-to-year scores.

“What most people will see is if their state has gone down relative to where they were last year,” Thomas said. “It’s one indicator of what’s going on in schools.

“It’s not really comparing apples to oranges, but it might be comparing red apples to green apples,” he said.

The state’s own assessment system, Arizona’s Instrument to Measure Standards, is taken by students statewide at different grade levels, depending on the subject matter: math one year, reading another and so on.

“When you look at all the indicators you can begin to see the mosaic that is public education in the state,” Thomas said of the AIMS reports.

The AIMS and NAEP assessments are very different tests for different purposes, said Molly Edwards, spokeswoman for the Arizona Department of Education.

“The tests have many technical variances that make comparing them difficult,” said Edwards. “A math test and another math test are not always the same thing but that is typically how they may be perceived.”

In addition to testing students, the national assessment also collects information about the background, education and training of the teacher whose students are taking the test. In every assessment since 2005, scores were higher for fourth- and eighth-grade students whose teachers held a master’s degree than for students whose teachers held a bachelor’s degree.

“That’s a variable we feel we can control in schools by enticing teachers to go back and get advanced degrees in their chosen field,” Thomas said.

While the data suggests that teachers with advanced degrees are improving student achievement, Goldstein said the improvement might not be due to one factor but could have a number of explanations.

“It could be possible that teachers that are better qualified are assigned to classes with better students,” he said.

But Thomas noted that any additional training is going to help a teacher become more effective in the classroom, whether it be to refocus on content or on particular teaching areas.

“When you are better in the classroom you’re probably going to see growth,” he said. “And that’s the name of the game right now is getting these kids college- and career-ready.”