Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Vaccine study aims to build common ground for parents, scientific community

PHOENIX – Parents deciding whether or not to vaccinate their children can be made to feel paranoid by health care providers for voicing any concerns.

To Ken Roland, research associate professor at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute, scientists should learn how to communicate better to bridge the gap with these concerned parents and build common ground.

“The problem that we have as scientists is we’re not really trained to be public speakers,” said Roland, who contributed to a recent study aimed at raising vaccine awareness. The institute collaborated with the Centre for the Study of Sciences and the Humanities at the University of Bergen, Norway.

The study examines ways to establish an open dialogue between members of the scientific community and members of the general public about scientific innovations such as new vaccines.

“We (scientists) tend to have a certain way of thinking about the world that’s cut-and-dry,” Roland said. “That’s not necessarily going to resonate with other people.”

Specifically, the study highlighted a new breed of vaccines known as Recombinant Attenuated Salmonella Vaccines. Roland explained that the bacteria salmonella is used as a vehicle to deliver proteins that could protect against a variety of bacterial infections like whooping cough.

But because they’re using salmonella, Roland said his team is trying to get out ahead of any public misinformation or misconceptions.

“Everybody knows salmonella makes you sick right, so why would you use salmonella?” he said.

But once scientists restructured the salmonella genome to avoid causing disease, Roland said “it turns out salmonella is very good at eliciting immune responses.”

Dorothy Dankel, a scientist at the University of Bergen who co-authored the study, said the study takes a “common-sense approach” that moves away from the typical, top-down model of the scientific community. She said there’s a misconception among scientists that if people have just the facts, they’ll automatically be on their side.

“Seventy percent of our decisions are emotional decisions,” Dankel explained. “You have to understand people’s values and speak to those values.”

That emotion could explain why a growing number of parents are choosing not to vaccinate their children.

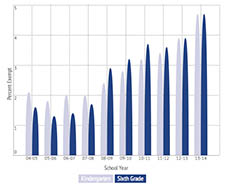

According to immunization data reports from the Arizona Department of Health Services, the percentage of children not being vaccinated for personal or religious reasons has steadily increased over the last decade.

In Maricopa County, the personal exemption rate for sixth-graders was 5.2 percent for the 2013-2014 school year, up 1 percentage point from the previous year. For kindergartners, the personal exemption rate increased from 4.3 to 5.1 percent in that same time.

Jessica Rigler, chief for the Bureau of Epidemiology and Disease Control at the department, said certain pockets of individual communities are primarily responsible for the dropping levels of immunized kids. She said it’s most common in communities with higher incomes and higher levels of education.

“We like to have our vaccination rates about 95 percent or above for most vaccine preventable diseases, because that’s the level of what we’d consider herd immunity,” Rigler said.

Herd immunity refers to a level of immunity achieved when enough members of a population are vaccinated against an infectious disease so they can protect others who haven’t developed immunity.

State Sen. Debbie McCune Davis, D-Phoenix, executive director of The Arizona Partnership for Immunization, called it a pattern of parents being more choosy about vaccinations when disease is less prevalent.

“Vaccines are really a victim of their own success,” she said. “When disease is prevalent, the vaccine is accepted. But after the vaccine produces the result where the disease is no longer visible, then the vaccine becomes the threat.”

In order to combat this pattern, McCune Davis said her organization produces educational materials for doctors to give parents a better understanding of how vaccinations work. But the most important thing, she said, is that doctors explain that the primary objective is to keep children healthy.

Stephanie Sergo, a stay-at-home mother of four in San Tan Valley, said that the decision to vaccinate is ultimately up to the parents.

When her youngest was 6 months old, Sergo said she had a gut feeling that she shouldn’t get the recommended booster shots because her daughter was experiencing problems breathing.

“If you get vaccines with children when they’re sick, it can cause complications. I feel like they don’t stress that enough at doctor’s offices,” she said.

After her daughter recovered, Sergo eventually did get her up-to-date on vaccines.

Sergo said her pediatrician was supportive but that not everyone is so lucky.

“A lot of times you can get doctors who treat you like a bad parent if you don’t want to do it,” she said. “They look at you like you have another head if you have any concerns.”

Sergo said she would welcome a movement from the scientific community to build an “atmosphere of understanding” with parents.

At ASU, Ken Roland said that was the motivation for participating in the study.

“We’re part of the same community as other folks, and these vaccines are going to impact us as well as everyone else,” he said. “We don’t want to put out something that’s going to harm anyone … we don’t have any special agenda.”