Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Number of openly nonreligious lawmakers remains constant

WASHINGTON – Most Arizona lawmakers feel a sense of pride when asked to give the invocation to open a House session, but Rep. Juan Mendez was gripped by a different emotion.

“I came in with a little bit of fear – not wanting to let myself be known,” said Mendez, a freshman Democrat from Tempe.

“Known” as an atheist.

Even as Americans become less religious and their tolerance for atheism is growing, there are still very few politicians who are openly nonreligious. They have to walk the thin line between their personal feelings and public image.

“There is such a stigma attached to being a nonbeliever,” said Lauren Youngblood, spokeswoman for the Secular Coalition for America.

This despite the fact that the fastest-growing religious group in the U.S. from 2007 to 2012 was religiously unaffiliated – or “nones” – according to a 2012 Pew Research report. It said the percentage of religiously unaffiliated U.S. adults grew from 15.3 to 19.6 percent in that time.

Nonreligious includes everything from atheists and agnostics to people who simply do not affiliate with any particular religion. But Pew said atheists and agnostics made up 5.7 percent of the adult population in 2012, accounting for about 13 million people.

But there is only one member of Congress who has gone on record as nonreligious: Rep. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Phoenix, was the only one to answer “none” when a 2013 Pew Research poll asked members of Congress about their religion.

Sinema’s office declined requests for an interview for this article.

“When she first got elected, everybody in our movement was very enthusiastic,” said Bishop McNeill, coordinator for a new secular political action committee. “But unfortunately … she has gotten some advice to stray away from that label.”

But experts say such reticence is understandable given the often-negative perception of atheists in this country and the long history of religion and politics.

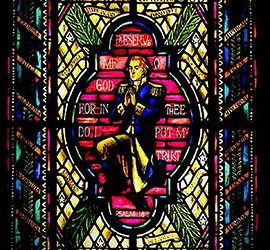

“Religion and politics have always gone together in America,” said Kevin Coe, a communications professor at the University of Utah and author of “The God Strategy.”

Ever since George Washington talked in his first inaugural address about “fervent supplication to that almighty being,” Coe said, presidents and other politicians have felt inclined to talk about religious faith.

Even though the Constitution bans a religious test for elected office, Coe said a de facto test is whether or not a candidate openly speaks to his or her beliefs.

That’s only fair that candidates share their religious beliefs, said Brent Walker, so voters can know where politicians stand morally.

Walker, the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, said that being a person of faith can be a plus in a country as religious as the U.S. – even though he conceded that some politicians overdo it to push policies.

But atheists, he said, remain “a very distinct minority in our country and I would argue a political disadvantage.”

Former members of Congress who have professed their lack of faith would agree.

In 2007, then-Rep. Fortney “Pete” Stark, D-Calif., became the first member of Congress to declare his atheism.

“I didn’t wear my atheism on my sleeve,” he said. “But I never went to prayer breakfast, either.”

After Stark came out, he met with some atheist groups but said he was surprised by how abrasive they were.

“I was sort of set back how aggressive and nasty they were towards anyone in another religion,” Stark said.

He said it should not matter what his, or any politician’s, religion is. That antagonistic attitude is one reason he and other lawmakers believe the label atheist has a bad rap.

Stark won two more elections as an atheist, but was beat in a 2012 primary race, leaving no open atheists in Congress.

Youngblood claims that 32 members of the current Congress have told her or others in the Secular Coalition for America, that they are atheist but cannot admit it for fear of political backlash.

Walker did not comment on the number, but said he would not be surprised if there were nonbelievers in Congress who claimed a faith.

To help chip away at atheism’s negative connotations, Youngblood said the coalition is encouraging atheists to “come out” – much as gays and lesbians did in the past.

But that may be easier said than done.

Former Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., made history in 1987 when he became the first member of Congress to willingly come out as gay, but it was not until recently, after he left office, that he talked about his lack of faith.

Frank said he quit professing any faith long ago, but because he was asked about his religion he would answer “Jewish.” While “none” might have been more truthful, Frank said, he did not want to appear as if he was turning his back on other Jews.

“(Politically) the barriers on nonreligious people have pretty much been dropped,” said Frank, who considers himself culturally Jewish. But he said making the leap from nonreligious to declaring “yourself an atheist goes eight steps further.”

Like Stark, Frank said atheist remains a harsh word.

That perception is the No. 1 problem nontheist politicians face, McNeill said. That is one reason for the creation earlier this year of the Freethought Equality Fund, which he coordinates, a political action committee to raise money for “electing secular leaders” and “defending secular America.”

The PAC does not have to report its financials to the Federal Election Commission until January, but it already has more than 50 donors, said Roy Speckhardt, executive director of the American Humanist Association, which operates the PAC. He said that means it can operate as a multicandidate PAC.

Chances for nonbelieving politicians are better – but still not good.

A 2012 Gallup poll found that 54 percent of voters would vote for an atheist in a presidential election, well above the 18 percent who said in 1958 that they would vote for an atheist.

But the same 2012 Gallup poll said 95 percent would vote for a woman, 94 percent for a Catholic, 80 percent for a Mormon and 68 would vote for homosexual. Atheist was the least-popular option.

Mendez said he does not shy away from the word atheist – but he did not want to be labeled the atheist lawmaker, either.

When he was called to offer the prayer in May, he first tried to get a secular lobbying group to give the invocation in his place, but that fell through. So he gave an invocation that started by asking all present not to bow their heads, but to look around at the others in the room.

“Let us cherish and celebrate our shared humanness,” Mendez said, “our shared ability for reason and compassion, our shared love for the people of our state, for our constitution and for our democracy.”

The next day, Rep. Steve Smith, R-Maricopa, asked House members to join him in prayer for “repentance of yesterday.” But Mendez said that was the only thing “that made it feel like I was doing something that I wasn’t suppose to be doing.” Otherwise, he said, he got positive emails and phone calls, and was stopped on the street by people thanking him for his prayer and message.

“I never meant to carry any type of flag,” Mendez said. “It was me just trying to be myself in that situation.”

Mendez’s “prayer” never addressed God, only humans, and it quoted Carl Sagan. And then, like any good atheist prayer, it ended not with “amen” but by saying, “thank you.”