Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Report: Number of border deaths remained steady, even as crossings fell

WASHINGTON – The number of people who died in Pima County while trying to cross the border from Mexico remained steady in recent years, even as the number of border-crossers dropped, according to a report released Wednesday.

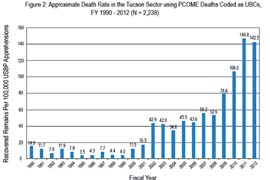

The study by the University of Arizona’s Binational Migration Institute attributed the steady death rate to the “funnel effect,” as more illegal immigrants funneled into the Sonoran Desert to avoid tighter security on other sections of the border. That put the smaller number of crossers in a deadlier place, said the report’s authors.

“People weren’t necessarily deterred,” said Daniel Martinez, a George Washington University assistant professor who began looking through data in 2005 while he was a University of Arizona master’s student.

“These deaths are deaths of people who are in the prime of their life,” Martinez said. “They’re searching for a better life and they’re willing to die to do that.”

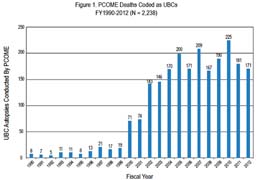

The report looked at more than 20 years of data from the Pima County Medical Examiners Office. It found that border deaths averaged 12 a year from 1990 to 1999. Between 2000 and 2012, however, that average number of deaths jumped to 163 per year, even though migration decreased during that time.

A crossing in a more-remote area of the desert can take three to five days, compared to two or three days in a less-hostile environment, Martinez said.

He said the study also found that more Central Americans have been crossing the border in recent years: Non-Mexican deaths jumped from about 9 percent between 2000 and 2005 to 17 percent from 2006 to 2012. Social and economic conditions in countries like Guatemala are driving more non-Mexicans to try cross the border, Martinez said.

At the same time, a fewer number of Mexicans crossed the border. While many had previously crossed the border for seasonal work, tightened border security has forced them to stay in the U.S. instead of going home.

The U.S. recession also played a role, with many Mexicans willing to wait for the economy here to improve before trying to come here, Martinez said. But Central Americans, who live in poorer economic conditions than Mexicans, don’t have that luxury.

Donald M. Kerwin, executive director of the Center for Migration Studies in New York, said the study shows how dangerous certain parts of the border are.

“It’s more dangerous to cross than it’s ever been,” Kerwin said.

Increased border enforcement has forced migrants to dangerous areas of the desert, leaving them vulnerable to “unscrupulous and dangerous smugglers.”

Bruce Anderson, a forensic anthropologist for the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office who participated in the study, said he did so because he wanted to make a difference.

“I don’t know how to change policy. I don’t know how to stop deaths. I don’t know how to change the status quo,” Anderson said.

But he can contribute his expertise of examining bodies and determining how the migrants died, he said, and then provide that data to researchers for their study, which he hoped would help policymakers with immigration reform.