Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Effort to preserve Mount Graham red squirrel features annual census

MOUNT GRAHAM – Each fall, Anne Casey bundles up in a sweatshirt, hat and gloves, throws a backpack over her shoulder, tightens her hiking boots and heads out to survey this southeastern Arizona mountain from top to bottom. Fifteen others join her.

Their goal: counting how many endangered Mount Graham red squirrels remain here based on piles of pine cone scales, known as middens, which the creatures leave to store green cones and other food for winter. Because the squirrels don’t hibernate, middens are essential.

“We hike to all the middens and we check out if they’re active or inactive,” said Casey, district biologist for the U.S. Forest Service. “We take a sample of all of the known historic middens and we go walk to them and visit every site.”

According to Casey, one midden represents one squirrel since the creatures are fiercely territorial.

Casey and the rest of the group split into teams of two or three and hike to known middens using a database created by Tim Snow, a non-game specialist for the Arizona Game and Fish Department. The teams also search for new or previously undiscovered middens.

The red squirrel census stems from controversy over the construction of a University of Arizona astrophysical observatory atop Mount Graham. An act of Congress that cleared the way for construction to begin in 1988 required UA to fund a monitoring program to determine whether the observatory harms the creatures’ population.

While the university’s commitment applies within 300 meters of the observatory and the road leading to it, the Arizona Game and Fish Department, along with the UA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and U.S. Forest Service, also conducts an annual survey of the entire area.

The Mount Graham red squirrel is indigenous to this mountain and is a subspecies of other red squirrels that live elsewhere in the Pinaleño Mountains, so-called sky islands of forest surrounded by desert.

“They’re a really interesting subspecies,” Casey said. “They’re only found here.”

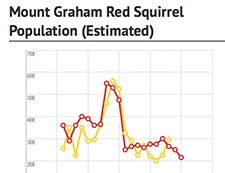

The last count, in fall 2013, found 272 Mount Graham red squirrels, an increase of 59 from the previous fall.

Snow, who created the Game and Fish Department’s red squirrel database, said the species has been isolated on Mount Graham for nearly 10,000 years and has grown genetically distinct. In the 1960s, so few remained that researchers thought they had gone extinct until a population was discovered in 1972.

“They tend to be smaller,” Snow said in a telephone interview. “Their life expectancy is a little bit different. They’re evolving.”

The most red squirrels ever counted on Mount Graham was 562 in 1999. The population has dwindled since due to habitat loss following two wildfires as well as insect outbreaks, among other factors.

Snow and others said the Mount Graham red squirrel’s average life expectancy has fallen to about a year and a half, while the species breeds at two years. Those that live long enough to breed face another obstacle: the squirrels are normally territorial and aggressive toward one another, and their window for breeding is only eight hours.

Ann Lynch, research entomologist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station, a U.S. Forest Service project with a presence on Mount Graham, said each challenge facing the Mount Graham red squirrel has a small impact but together they threaten the habitat and population.

Lynch said one of the biggest challenges is insects such as the bark beetle, which weakens pine trees that the squirrels rely on.

“Those insects killed 85 percent of the trees,” she said. “But the population as long as we’ve known it has never been a big population.”

That is why groups partnering in the annual census worked with the Phoenix Zoo to create a 10-year pilot breeding program.

The zoo has six Mount Graham red squirrels that eventually will be returned to the wild, but it must surmount the same obstacles the species faces back home, starting with the fact that squirrels put in the same cage would likely fight to the death except at mating time.

“What we’re challenged with in this breeding program is to figure out that day and what eight-hour window we have in that day to put them together safely so we don’t get that aggression,” said Stewart Wells, the zoo’s director of conservation.

Meanwhile, a UA lab atop Mount Graham monitors the squirrels year-round.

John Koprowski, director of the university’s Mount Graham biology program, said preserving the species is important for other animals that have evolved to rely on the middens the red squirrels create.

“People could let them go extinct,” Koprowski said in a phone interview. “You’re not really necessarily just losing a single species, but when a species is lost it impacts many other things within that environment.”