Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Prosecutors: Supreme Court ruling in Arizona killing could speed death-row cases

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling that a mentally incompetent Arizona death-row inmate cannot indefinitely delay his case will speed the “scandalously long” pace of similar cases, the state’s attorney general said Thursday.

Attorney General Tom Horne said the lengthy process of appeals in capital cases hurts the family members of the victims, who have to wait years to see justice served.

“They are, in fact, victimized a second time by the court system,” said Horne, who believes the high court’s ruling in the case of Ernest Gonzales could change that.

But defense attorneys noted that the Supreme Court’s ruling still allows delays on a case-by-case basis. Now, however, they must show that a defendant can be returned to a point where he is competent enough to assist in his defense.

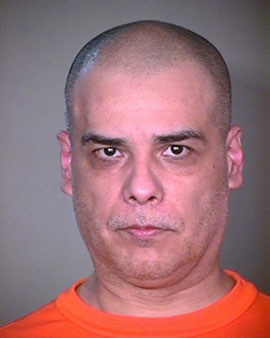

A federal appeals court had ruled in 2010 that Ernest Gonzales‘ appeal could be delayed indefinitely because he was not competent to assist his attorneys. It was that ruling the Supreme Court reversed on Tuesday.

Gonzales was convicted of the 1990 stabbing death of Darrel Wagner in front of Wagner’s family, according to an Arizona Department of Corrections summary of his case.

Wagner, his wife, Deborah, and their 7-year-old son had returned from dinner when they found Gonzales robbing their Phoenix home. While the son was sent for help, Gonzales began stabbing Darrel Wagner. When Deborah Wagner jumped on Gonzales’ back in an effort to defend her husband, she was also stabbed.

Darrel Wagner died from stab wounds to the heart and lungs, while Deborah Wagner spent five days in intensive care for her wounds.

Gonzales was convicted of murder in 1991 and sentenced to death.

In the subsequent years in prison while his case was appealed, Gonzales has become irrationally suspicious of his defense lawyers and refused to see them, according to a court document submitted by the American Civil Liberties Union.

It is common for death-row inmates to develop mental illness or for mental conditions to be exacerbated on death row, said Brian Stull, an ACLU lawyer who submitted the document.

These conditions are caused by the “anguish of knowing you are going to be executed by the state and not knowing when that’s going to be,” Stull said.

Defense attorneys argued that Gonzales’ condition had gotten so bad that he was not able to help in his defense. A federal district court disagreed and said Gonzales’ case should proceed. But the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overruled the lower court, saying that letting Gonzales’ case move forward would “eviscerate the statutory right to counsel” in the Sixth Amendment.

“It has always been our position that a client and an attorney be able to communicate,” said Dale Baich, the assistant federal public defender for Arizona.

The Supreme Court reversed the circuit court Tuesday, ruling that the capital appeals process can proceed without the participation of the defendant and it would not violate the right to be represented by an attorney.

“I think it’s a highly significant case,” said Kent Cattani, an assistant Arizona attorney general who deals with capital cases.

Nationally, there are 700 other cases at the same stage of appeal as Gonzales’ case, Baich said. Of those 700, he said, 10 are on hold because of the defendant’s mental incompetency.

Despite the high court’s ruling, the defense could still seek another stay in Gonzales’ case by arguing that he cannot be defended using only court documents, as prosecutors have argued, and that his competency will return.

Baich would not say whether he planned to ask for another delay in the case, but he did say that this is not the last step in the process. Defense attorneys will raise possible errors that may have occurred during his hearing and sentencing, for example, and before any execution can take place a final hearing on the defendant’s mental competency must be held.

A lengthy appeals process for a death sentence is common. The average number of years nationwide between conviction and execution in 2010 was 15 years, according to the Death Penalty Information Center, a national nonprofit.

In Gonzales’ case, Cattani said there are no issues that require the defendant’s input and the case may be appealed based solely on the court documents.

“The case has to go forward,” Cattani said.