Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Small gifts make big – and murky – difference in campaign finance transparency

WASHINGTON – Arizona was fairly giving this election season, kicking in at least $16 million to presidential candidates, according to the Federal Election Commission.

“At least” being the operative phrase.

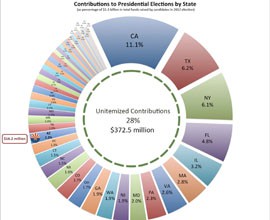

The FEC does not require campaigns to detail the source of every nickel and dime donated to a candidate, even though unitemized “small gifts” accounted for $372.5 million of the $1.3 billion donated to presidential campaigns in the last election.

The enormous sum of these “stateless” contributions makes it impossible to tell exactly how much Arizonans – or anyone else, for that matter – invested in federal elections, experts say.

“There’s a large pool of money that’s been raised that you can’t account for where the donors live,” said Brendan Glavin, a Campaign Finance Institute analyst.

Candidates for federal office are only required to disclose information on donors who have given more than $200.

“You can count up the number of unitemized donors from the FEC data, and you can know the unitemized total,” Glavin said. “But if somebody didn’t give more than $200, they just put that in a lump sum and don’t report where that came from.”

Unitemized gifts played a lesser role in congressional races: In Arizona’s Senate race, they accounted for 9.5 percent of fundraising; in the House races, 13.1 percent.

But to some campaign finance experts, small gifts are a benign example of mystery money in elections especially after the emergence of super political action committees and “shell” groups whose spending in this cycle dwarfed the unitemized small givers.

“The biggest struggle is with outside spending activity,” said Craig Holman, a lobbyist with Public Citizen. “If we could get as good a picture of spending by outside groups as we do from candidates, we would have a reasonably good disclosure system.”

Holman said campaign disclosure rules aren’t perfect, but they do keep campaigns on their toes.

“There are holes in that reporting process, but those holes are not as big a concern,” he said.

The Center for Responsive Politics reports that outside groups spent at least $1 billion in the election – more than $600 million from super PACs and millions more from political parties, unions, individuals and other groups.

In Arizona’s congressional races, outside groups spent at least $36 million in independent expenditures on this fall’s elections, according to the FEC.

But that still does not account for all outside spending.

Some groups, like non-profit “social welfare organizations,” do not have to file an accounting of their financial activities for months. When they do, some of their ad spending won’t be disclosed depending on the content, medium and timing of the ads.

Those expenditures are part of the reason Holman is glad there are laws regulating campaigns, even if they are imperfect.

“We don’t get a full and completely accurate picture, but candidates are required to make a reasonable effort with disclosure,” Holman said.

The FEC campaign guide states that “when making solicitations, committees and their treasurers must make ‘best efforts’ to obtain, maintain and report the name, address, occupation and employer of each contributor who gives more than $200 in an election cycle.”

Committees can report that information voluntarily, and sometimes do, said Liz Bartolomeo, media director for the Sunlight Foundation.

“It’s all how the campaign files those small donors,” she said in an email. “The FEC should follow up with the campaign and ask that the information be completed, but sometimes it doesn’t.”

For disclosure advocates, simply being able to flag holes in the disclosures is a step in the right direction, given the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Citizens United case. The court said in that case the political spending is a form of speech and cannot be constrained.

Jerry Goldfeder, an election lawyer and professor at Fordham Law School, noted that one aspect of the Citizens United ruling is often overlooked.

“The court says that disclosure is still something that is lawful and it’s a positive aspect of campaign finance law,” he said.

And like others, he said an imperfect database is still a starting point to transparency.

“This just allows people to review and research that which is already disclosed,” Goldfeder said.