Puerto Rico: DOJ report on the Puerto Rico Police Department reveals an ‘Agency in Profound Disrepair’

SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico — Three women in Marcia de Jesus’ house laugh and chatter as they prepare the day’s food in a cramped kitchen.

The house sits on a narrow street of Barrio Obrero, a heavily Dominican working class neighborhood in the Santurce area of San Juan. De Jesus runs a neighborhood eatery out of the house.

Sunlight streams through slats in an old wooden fence, lighting a patio where the little restaurant’s employees laugh and socialize with locals who enjoy home-cooked meals of rice, beans, chicken, pork and steak. They sometimes drop small scraps for a mangy looking but affectionate cat.

But the revelry evaporates when uniformed members of the Puerto Rico Police Department come in for food. De Jesus still serves the police, but she will never get over what they did to Joel, her 26-year-old son.

“It’s very difficult” when the police come in, she said. “[N]ot all police are the same. But it is very difficult for me.”

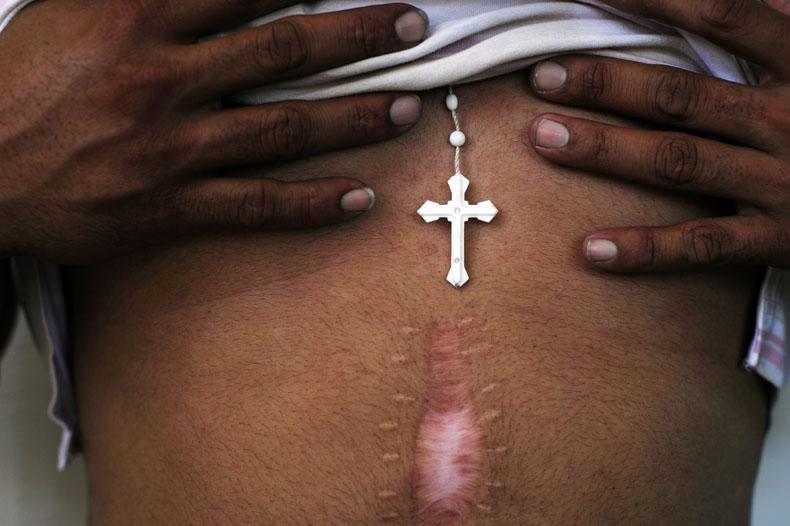

In May 2009, Joel Feliz de Jesus had been drinking at a party and was walking on the street when he got into an argument with a few police officers. He remembers asking them why they were looking at him and telling them to leave him alone. He recalls a cop he swears was seven feet tall approaching him and telling him to put his hands behind his back. His next memory is waking up in a hospital with a fresh scar running the length of his torso, the result of surgery to repair severe internal injuries his family claims were inflicted by the police that night.

Claims like those made by the de Jesus family aren’t uncommon in Puerto Rico. The 17,000-member Puerto Rico Police Department – the second largest police force in the United States and its territories – has been under investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice since July 2008.

In a report released in September 2011, the Department of Justice said its investigation uncovered a litany of major problems.

“The amount of crime and corruption involving PRPD officers … illustrates that PRPD is an agency in profound disrepair,” government lawyers wrote.

The most prevalent and troubling problems include allegations of excessive use of force by police and a sustained disregard for the constitutional rights of many of the island’s 3.7 million residents. The Department of Justice noted that more than 1,700 police officers in Puerto Rico — roughly 10 percent of the force — were arrested between January 2005 and November 2010. That’s nearly triple the number of officers arrested in the New York Police Department, a force more than double the size of the Puerto Rico’s police department, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union.

These problems come at a time when crime is soaring in Puerto Rico. The island saw a record 1,136 murders in 2011, much of it attributed to a burgeoning drug trade. Violent crime of all types is up sharply over the last few years.

Top police officials and Puerto Rico Gov. Luis Fortuno’s legal advisors said the police department has room for improvement but the major cases highlighted by media reports and the Department of Justice are isolated and not representative of the entire police force. Government officials claim they’ve updated police training curricula, upgraded technology, increased police officer pay and created citizen interaction committees.

Multiple follow-up emails and phone calls to the police department and the governor’s office asking for specific data to back up these claims have gone unanswered.

Street-level police officers have a more nuanced view of the report. Many agree with some of the overall points — political alliances driving promotions, poor leadership — but say the dramatic allegations of abuse, corruption and discrimination are wildly exaggerated.

The Justice Department says the police department’s failings impact a wide range of Puerto Rican communities.

But alleged brutality in Dominican communities like Barrio Obrero was one of the investigation’s initial focuses, according to Luis Saucedo, the acting deputy chief of the special litigation section of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division and one of the lawyers who is working the case.

Dominicans are by far the largest minority group in Puerto Rico. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, there are roughly 68,000 Dominicans living in Puerto Rico but the real number is at least double, maybe triple that amount, according to Dominican activists, lawyers and even Saucedo.

But Saucedo said the Justice Department can’t come to any conclusions on the extent of police abuse in the Dominican community because of a shortcoming in record keeping.

“The problem … was that Puerto Rico does not keep sufficient data to be able to know whether they’re enforcing the law in a way that’s fair and equitable,” Saucedo said.

When Justice Department lawyers asked the PRPD how it knows it’s not profiling Dominicans, the department didn’t “have the systems to be able to demonstrate that they’re not.”

A key issue is that the Puerto Rico Police Department incident reports allow officers to identify people as Indian, white, black, Asian, Hawaiian or as a native of Alaska, but not Dominican.

“The data just isn’t being captured,” Saucedo said. “Supervisors aren’t being given the tools to be able to make sure that it isn’t happening. What was clear was that the allegations were being made and that the complaints, many times, were not being investigated.”

A lack of quantifiable data doesn’t change the minds of people who say that PRDP abuse and harassment of Dominicans is widespread and well known.

William Ramirez, the director of the American Civil Liberties Union in San Juan, says abuse of Dominicans by the police department has gone on for years, and the problems are systemic, not isolated.

“There’s an animosity toward the Dominican community on the part of many police officers,” Ramirez said. “I’m sure it’s not all, but it’s enough of them that it’s a problem.”

Enrique “Kike” Cruz, a popular Puerto Rican conservative radio host who supports the Fortuno administration, has been studying problems with the police for the last seven years.

“It’s unfortunate what’s happened in the Dominican community but what happened to the Dominicans also happens to Puerto Ricans,” he said. “It’s the same ignorances, the same lack of respect. The ineptitude of the police does not discriminate.”

Cruz added that the Department of Justice exaggerated some of the problems but there’s no way to refute it.

“(The Puerto Rico Police Department) statistics are ridiculous, they’re not good they’re not reliable,” he said. “The Puerto Rico police cannot defend themselves because they have such poor statistics.”

Despite a lack of quantifiable data, the Justice Department highlighted several major incidents of misuse of force and brutality.

In 2009, police clashed with Dominicans in a squatter community called Villas del Sol, located in Toa Baja, a town located southwest of San Juan. A weeks-long police presence in the community resulted in a violent confrontation, where women and children were pepper sprayed, according to the Department of Justice.

In August 2006, a Dominican man named Ignacio Santos Rosario was at a bar in Rio Piedras. Also at the bar was PRPD officer Gregorio Matias Rosario. According to federal court records, Matias was talking badly about Dominicans and Santos asked him to show some respect. Matias then pointed his police-issued gun at Santos and called for backup. Santos tried to leave the area but Matias shot him twice in the leg. Santos alleged that additional PRPD officers arrived on the scene and began beating him as he lay on the ground. In 2009, Santos’ civil rights case was dismissed after the parties entered into a confidential settlement.

Also in 2006, a Dominican man named Felix Escolastico Rodriguez was parking his car in Rio Piedras. According to court records, several officers approached him and began beating him. As they were attacking him, at least one of the officers unloaded a string of racial and ethnic slurs against Dominicans. In 2010 Escolastico settled out of court with the police officers.

High-profile incidents will always get a lot of attention but activists and the Justice Department say abuses and discriminatory policing happen on a regular basis.

“Evidence suggests that PRPD officers violate the rights of individuals of Dominican descent or appearance through targeted and unjustifiable police actions,” Justice Department lawyers wrote.

The ACLU’s Ramirez says Dominicans in Puerto Rico, the majority of them undocumented, can’t fight back or go public with allegations of abuse in many cases.

“The first (worry) is deportation,” Ramirez said. Documented Dominicans can also face police backlash, he added. “You become a target for police, you’re a troublemaker. You’ll be watched, and at the slightest thing that they might think constitutes a crime, you become a victim. You’ll get set up.”

The Department of Justice reported allegations of Puerto Rico Police Department officers planting drugs on people, as Ramirez suggested. Jose Rodriguez, the spokesman for the Dominican Committee on Human Rights, said that could have happened in Joel Feliz de Jesus’s case.

Feliz de Jesus’s beating allegedly took place in May 2009. Two months later, federal court records show that the U.S. Postal Inspection Service accused Feliz de Jesus of receiving 280 grams of heroin in the mail from Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. A judge signed an arrest warrant on Aug. 3, 2009, and Feliz de Jesus spent six days in jail. On Aug. 24, the United States Attorney’s office dismissed the charge. Feliz de Jesus denies that the heroin was his and said he’s not sure why charges against him were dropped.

Multiple calls and emails to the U.S. Attorney’s office were not returned and the police did not respond to multiple records requests for any information related to Feliz de Jesus.

Feliz de Jesus’s case is isolated, said Puerto Rico Police Sgt. Iran Sanchez. Sanchez is an 11-year veteran and one of a handful of sergeants responsible for running the Barrio Obrero precinct. Sanchez, who has also worked in police precincts in San Juan and nearby Bayamon, said most of his officers are good people and that discrimination against the Dominican community is isolated to a relative few officers.

“There may be some officers that will discriminate against people from other nationalities, but believe me, the majority of police officers here do not,” Sanchez said. “(The Department of Justice) is trying to show that we’re, to some extent, a racist police department when it is not.”

Lorena Garcia Rios, a legal advisor in the Puerto Rico Police Department Superintendent’s office, said discrimination against the Dominican community is not widespread.

“The media sometimes exaggerates it,” she said. “As a whole, it’s not, like, the current practice. It’s minor, isolated incidents.”

While Sgt. Sanchez dismissed claims from Dominican activists and community members alleging widespread discrimination, he said there are a host of problems with the police department.

He pointed out the police force’s “merit” promotions system. Until December, officers could be promoted by a superior “on merit” rather than by examination. The system was rife with officers moving up the chain of command based on who they knew and their political affiliations, according to Sanchez.

“Not every time (officers are promoted) they are actually qualified and prepared to be in a supervisory position in police work,” Sanchez said. “A lot of officers were going up in rank because of favors. As simple as that.”

The Department of Justice noted this problem in its report. Between January 2008 and September 2010, 1,615 of the 1,707 of officers promoted to sergeant – 95 percent – were promoted without testing.

The non-testing, “merit system” was largely the result of Puerto Rico’s unique system of an all-powerful governor. The governor appoints the superintendent, but also directly approves leadership positions several layers down into the bureaucracy. The idea that politics and alliances rather than good work enhances careers has real consequences on the street, according to the Department of Justice.

“(It) fosters a dysfunctional professional atmosphere and encourages subordinates to question the qualifications and competence of command officers,” Department of Justice lawyers wrote. The system also makes it hard for lasting reform because of the massive turnover and reassignments with each new administration.

The consistency in the leadership of the police department has been further strained by constant turnover in the superintendent’s office. Superintendent Emilio Diaz Colon resigned March 28, and Gov. Fortuno appointed Hector Pesquera to replace him. Pesquera, the former leader of the FBI office in Puerto Rico, is the 10th superintendent since 2000.

Alfonso Orona-Amilivia, a deputy adviser to the governor for legal affairs, said the police offered a sergeant’s test in December 2011 to give worthy, qualified officers a fair chance to move up in rank, and roughly 534 out of 2,000 that took the test passed. Sanchez said the department brought the test back because of the Department of Justice investigation, which began three years earlier. Orona and Garcia deny that was the motivation.

Other officers complained about a culture that rewards political affiliations and alliances over good police work. Many current sergeants and higher-level supervisors benefited from this system, and are reluctant to change it, they said. And when officers who don’t play the game speak up, they’re punished with arbitrary transfers far away from their hometowns and denied promotions.

“We’ve always said the police in Puerto Rico is directed by inept people,” said Luis D. Mercado Fraticelli, a 33-year veteran of the police force who retired as a first lieutenant in 2004. Mercado is the president of the Sindicato Policias Puertorriquenos — the Union of Puerto Rican Police — which represents roughly 1,300 officers and is one of five police unions in Puerto Rico.

Mercado said he and the union support the current government but are adamant that rampant politicization over many years has created an entrenched leadership group that is resistant to change or suggestions that threaten its power. The Sindicato has also called for higher pay for police officers, leading a demonstration in November 2011 in San Juan where more than 6,000 officers demanded raises promised to them over many years.

The Sindicato points to the plight of one of its regional directors as an example of the system. Sgt. Jose Cruz Martinez, a 20-year veteran of the police force, took simmering internal complaints of outdated equipment and unpaid overtime to the press two years ago. Three days later, Sgt. Cruz was transferred from his position in Ponce — a city on the south coast of the island close to his home — to a prison many miles away. Sgt. Cruz has faced seven additional transfers since then, according to the Sindicato.

The police department has not responded to several requests for records on Sgt. Cruz’s transfer orders.

The resulting environment within the police department is behind many violations of civil rights, said Sgt. Jose Marin Martinez, the vice president of the Sindicato.

“Every time a police officer makes a mistake, it’s because they don’t have any way to deal with the pressure,” he said. “It’s not because police aren’t trying, it’s not because officers aren’t given instruction. (Police) fail because they are under big pressure.”

Miguel Pereira was the superintendent of the Puerto Rico Police Department in 2002. Now an opposition-party candidate for the Puerto Rico Senate, Pereira said street-level police officer morale is low and has been for years.

“The sense of frustration that policemen have about the value of their own work, and self-worth, is very low,” he said. “They do not feel supported by the establishment … they feel like they are in this by themselves.”

Couple that context with poor training and a political patronage system that rewards all the wrong things and problems are bound to occur, Pereira said.

“Angry and violent reactions (against the public) should be condemned, and I’m not suggesting we don’t, but it needs to be understood,” Pereira said. So when an officer is out on the street and someone happens to cross him, “the reaction is going to be instant and violent.”

Orona, governor Fortuno’s deputy advisor for legal affairs, said the governor is trying to correct the myriad problems facing the police department. He said police officers’ pay has been brought up to scale but didn’t respond to multiple requests to provide data to prove it. He also said that reform is a complex process because of the varied needs of places like urban San Juan compared to mountain regions or smaller towns.

“We have a mixture of needs within the police and I think that’s the main challenge, Orona said. “Maybe other administrations didn’t understand the importance of actually seeing the police as a whole. There have been some years within some administrations where there has been improvement but I think that the structural improvement that has been going on in this administration is the one that’s going to have a lasting result and lasting improvement in the police department.”

The Department of Justice and Puerto Rico are negotiating how reforms will actually take place. The federal government prefers a court-enforceable agreement to mandate reforms regardless of Puerto Rico’s political leadership.

“[I]n the end … the only instrument that I think is going to carry us through the long haul is a court-enforceable agreement,” said Saucedo, one of the Department of Justice’s lawyers negotiating with Puerto Rico. “We want some assurance that [reforms] are going to be carried out.” That process, known as a consent decree, would require an independent monitor agreed to by both the Department of Justice and Puerto Rico to watch the process and report to a judge.

The government of Puerto Rico doesn’t think a court order is necessary.

“Cooperation is key, and a consent decree is usually when some of the jurisdictions have not been cooperating,” Orona said.

Puerto Rico Secretary of State Kenneth McClintock called a consent decree totally unnecessary.

“If someone would do that it would only be for political reasons to show that they were doing something,” McClintock said, “because we are reacting positively, much better than anybody ever has.”

All involved — from the Department of Justice to the government of Puerto Rico to the lawyers and activists — agree that meaningful reform will take years. But for people like Feliz de Jesus and his family, the damage is already done. His mother said all she wants is justice, and for the police to respect the community.

But Yarmesha Rios de Jesus, Joel’s 16-year-old sister, represents the future. She said the Puerto Rico Police Department seems to think they have more rights than Dominicans because they’re Puerto Rican.

“They don’t respect the people,” she said. “They should be the example. They’re not like what they look. They’re supposed to protect the people.”

Does she trust the police? “No. Not at all.” Will she ever? “Never.”