Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Concussions an often overlooked problem in girls’ sports

TUCSON – Corina Gallardo was a straight-A student through junior high. But by her freshman year, she couldn’t focus for long and her grades suffered.

“I was always tired, I was always sleeping and I had headaches,” she said. “And every time I ate, I would vomit.”

The school nurse added up the symptoms and told Corina’s mom to get her daughter checked for a traumatic brain injury.

A foot to Corina’s face during a cheerleading stunt months earlier had left her with a concussion.

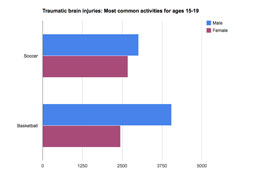

Concussions are most common in high school football, but girls’ sports carry risks as well: headers in soccer, elbows on the basketball or volleyball court, girls colliding in lacrosse or softball.

According to several Arizona doctors, concussions in girls’ sports are often overlooked.

“Girls are less identified. They don’t complain as much,” said Dr. Sydney Rice, a developmental behavioral pediatrician who focuses on brain injury.

“A misconception is that boys can be tougher, but the symptoms are the same in girls,” said Dr. Dan Mullen, a Mesa surgeon specializing in sports medicine. “It’s important not to discount a girl’s symptoms as a lack of toughness just because she’s a girl.”

When Corina got hurt in 2008, her eyes were swollen shut.

“I would bump into the walls,” she remembered.

Three different doctors suggested treatments ranging from allergy shots to thyroid medication, according to Corina’s mom, Brenda. At one point, Corina’s parents tested her for illegal drug use.

“I’d be walking down the school hallway and totally blank on how I got to school,” Corina said. “I’d have to call my mom to find out where I was supposed to be.”

In the meantime, Corina was suffering mood swings and frustration from not being able to comprehend and memorize like she was used to. She also lost her sense of smell.

“The diagnosis was a relief because we just didn’t know what was going on,” Brenda Gallardo said. “They even thought she was bulimic because she was throwing up, so we went to a dietician.”

Because Corina continued to cheer in the months before she got a concussion diagnosis, she likely experienced what is called second-impact syndrome.

This is the biggest long-term danger, according to Rice.

“Look at the sport and look at risks. If she is injured, have a low threshold for pulling her out,” Rice said. “Missing a few games might allow her to heal and have a normal life. The risks of not stopping are great.”

To avoid second-impact syndrome, Rice gives parents and patients a list of sports divided into three columns: red for collision sports that should be avoided, such as field hockey, martial arts and soccer; yellow for maybes such as gymnastics, volleyball and bicycling; and green for safe activities such as archery, running, swimming and golf.

“Dedicated athletes don’t want to let the team down,” Rice added. “They feel they should gut it out. And that’s exactly the opposite of what we want to teach them.”

With last year’s passage of SB 1521, Arizona coaches in most youth sports must take a concussion class. The requirement has already helped, according to Mullen, the Mesa surgeon.

“All of the coaches now speak the language that used to be reserved for team doctors and athletic trainers,” said Mullen, who sees at least one new concussion patient a week. “There’s less of that bravado, suck-it-up mentality and there’s a more caring environment.”

Four years after her concussion, Corina Gallardo is a freshman at the University of Arizona, studying journalism and psychology.

“I don’t think I’ll ever be back to where I was,” she said. “I still get headaches and have a hard time remembering. But it’s a lot better.”