Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Dust storms have medical group highlighting Valley fever threat

MESA – Corey Schubert describes himself as a healthy guy, but one night last October he had such a severe pain on the left side of his chest he could barely move.

“I couldn’t even grab the remote control,” the 35-year-old said.

When the pain was worse the next morning, Schubert drove himself to the emergency room and discovered he had what doctors call a “white out.”

“My left lung on the X-ray was completely white from pneumonia, which is a typical symptom of Valley fever,” he said. “It was truly awful – and what I found most eye-opening was how easy it would be to think it could be a heart attack or pneumonia.”

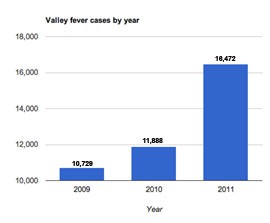

Since a gigantic haboob in July 2011, Banner Health, where Schubert is a public relations specialist, has seen an epidemic of Valley fever, which can be deadly in patients who have compromised immune systems.

“It’s just now slowing down,” said Dr. Larry Spratling, a pulmonary disease expert and chief medical officer at Banner Baywood Medical Center.

A fungus that grows in dry soil causes Valley fever, which primarily attacks the lungs and leads after a few weeks to symptoms similar to the flu.

Misdiagnosis of Valley fever can be a problem because sufferers can wind up being treated the wrong illness, delaying recovery, said Shoana Anderson, chief of the Arizona Department of Health Services’ Office of Infectious Disease Services.

“It’s why we encourage people who are coughing, exhausted and running a fever to ask to be tested for Valley fever,” Anderson said.

Ironically, 70 percent of the people living in Arizona will get Valley fever but never get sick enough to get it officially diagnosed, Spratling said.

“I don’t want to drive people away; I like it here,” Spratling said. “But if you live here long enough, you are likely to get it.”

Dogs commonly get Valley fever too.

“I even treated a gorilla at the zoo years ago,” Spratling said.

But it’s the pets that are helping public health professionals pinpoint where Valley fever originates.

“People go hiking, they go to work, they’re at home, so they may not be sure where they got infected,” Anderson said, “but if their dogs are sick, it helps us understand where to look.”

While Valley fever is on the rise, Anderson and Spratling both said that higher awareness and more testing may mean cases are recognized now that might not have been several years ago.

Schubert thinks his case of Valley fever can be traced to one of the smaller haboobs that blew through his Gilbert neighborhood last summer.

“I got caught out in the dust storm for about five minutes,” he said. “I remember thinking I breathed enough dust that it couldn’t be good.”

At the state Department of Health Services, Anderson doesn’t blame dust storms entirely for the rise in Valley fever.

“We are exploring connections, and the storms are a concern for us, so we urge people to stay inside or wear a mask,” she said. “But because the Valley fever spores can incubate for three to four weeks, it’s a challenge for public health.”

Dr. John Galgiani, director of the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence, said a 37 percent increases in cases last year didn’t follow the dust storms.

“I predicted 3,600 extra cases following last July’s storm,” he said in a telephone interview from Tucson. “But no such bump occurred. The rise came week by week.”

Galgiani said a promising drug called Nikkomycin Z could reach the market in five to seven years.

The drug will be too late for Corey Schubert and the many others who have suffered from Valley fever.

Schubert is fully recovered now but will stay inside even if there’s a threat of a dust storm.

“For me, it’s not so much that I will catch Valley fever again,” he said. “I just don’t want to breathe that stuff.”