Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Feds list two Arizona fish as endangered, name 710 miles of ‘critical habitat’

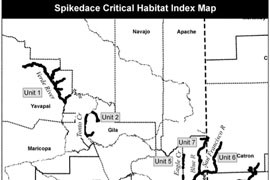

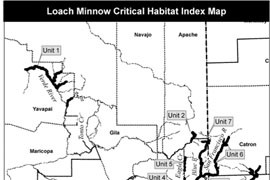

WASHINGTON – The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service downgraded two fish species to endangered Thursday, designating more than 700 miles of Arizona and New Mexico waterways as critical habitat in the process.

The designation means the spikedace and the loach minnow, previously listed as threatened species, are now considered in danger of extinction through loss of habitat and threats from nonnative predators.

The move designates hundreds of miles in Apache, Cochise, Gila, Graham, Greenlee, Pinal and Yavapai counties in Arizona, as well as parts of New Mexico, as critical habitat for the 3-inch fish. That means agency approval will be needed for projects in the area.

Conservation groups welcomed the move, which they said gives the species a chance at recovery.

“These fish really are in trouble, so we’re glad to see that’s being recognized,” said Noah Greenwald, the Center for Biological Diversity‘s endangered species program director.

“You really can’t protect and recover endangered species without protecting the places they live,” he said.

But Ben Alteneder of the Arizona Wildlife Federation noted that the service’s designation Thursday excluded habitat on tribal lands, on Fort Huachuca and on private land owned by the mining company Freeport-McMoRan.

“In reality, we need those private land owners to help us facilitate the safe recovery of those species,” Alteneder said.

The fish are close to extinction in part because of predation by nonnative species. Steve Spangle, a Fish and Wildlife Service field supervisor, said the spikedace and loach minnow never developed characteristics to evade predators, leaving them vulnerable when settlers introduced other species – or “big fish that eat little fish.”

“They’re very vulnerable,” Spangle said. “They’re essentially sitting ducks.”

He said the fish have also lost habitat to dams, mining, livestock grazing and other activities.

“These fish are adapted to free-falling creeks. When they become lakes – for instance behind a dam – that is no longer suitable for these two fish,” he said.

Greenwald said he was sorry that some lands had been excluded from the critical habitat list, and hopes those landowners work to help the fish recover.

“The service should monitor those areas where they’re relying on others for management,” he said. “We’ll be watching that closely.”

Tribal officials could not be reached Thursday, but a Fort Huachuca spokeswoman said the Army is already helping by reducing its groundwater consumption. Tanja Linton also said in an email that the fort has a record of managing other endangered species, “dramatically” increasing the number of lesser long-nosed bats on the base, for example.

Freeport-McMoRan said it has developed a management plan with the service that gives the spikedace and loach minnow greater benefits than would come from the critical habitat designation.

“As a result of these commitments,” said company spokesman Eric Kinneberg in an email, Freeport-McMoran land on Arizona’s Eagle Creek and San Francisco River and on New Mexico’s Gila River and Mangas and Bear creeks could be excluded from the critical habitat list.

But a property-rights advocate worried Thursday that the critical habitat designation gives the federal government “virtual veto power over any land use.”

“Habitat that is designated as critical cannot be modified in an adverse way without federal approval,” said Reed Hopper, a principle attorney for Pacific Legal Foundation. Those modifications could range from dam development down to cutting trees along a water bank, he said.

It can be a problem if the government applies the designation and its restrictions too broadly, Hopper said, noting that he has heard of people getting letters after they built fences in areas that were critical habitat for endangered birds.

“The agency can be unreasonable in its demands that a critical habitat be maintained,” Hopper said.

Alteneder said private landowners can head off the critical habitat designation and help the fish by entering into “safe-harbor” agreements with the Fish and Wildlife Service.

“That’s a tool we encourage using, and we’d be happy working with anybody on nonfederal land who would be interested in doing a safe-harbor agreement,” the service’s Spangle said.

Alteneder said there is still hope for the fish if conservation groups work to raise public awareness, noting that Apache trout and Gila trout made their way back from endangered-species status.

“It’s never a good thing when a species goes on an endangered list,” he said. “Involvement by a variety of conservation groups . . . can really move the ball forward.”