Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Diabetes ‘pandemic’ takes severe toll among state’s border-area Hispanics

SAN LUIS – Several dozen residents of this southwestern Arizona community crowd a seminar room to hear Dr. Bonifacio González Castro, vice-director of the general hospital just across the border, talk about how to manage diabetes.

As he starts, González removes his glasses and asks in Spanish: “Are a few of you diabetic?”

Many laugh. Nearly everyone in the audience, comprised mostly of older Hispanics, raises a hand.

“Well, then you bet we have a problem,” González says.

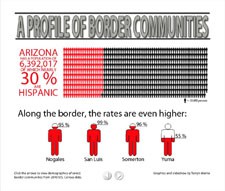

Diabetes is a growing problem among all ethnic, age and socio-economic groups, but experts, officials and advocates say it has reached alarming proportions among Hispanics living near the U.S.-Mexico border, driven by factors including obesity, poverty, a lack of health coverage and poor diet.

González urges his audience of nearly 50 to seek medical advice on the disease, start taking care of themselves and control their weight.

“I say that walking at least 30 minutes a day, we can do it,” he tells them.

González came from Mexico, where the disease is even more common than on the U.S. side, at the invitation of Campesinos Sin Fronteras, a nonprofit that educates low-income Hispanic families in Yuma County’s border communities about diabetes and other chronic diseases.

Campesinos Sin Fronteras workers have the audience stand and do stretches. The crowd starts moving their arms in circles, then raise their arms and shake their wrists under the supervision of the staff.

The nonprofit educates around 500 people each year about diabetes management, and its staff visits those who cannot come to its offices. It also provides free blood glucose and blood pressure tests and organizes exercise challenges between residents of Somerton and San Luis.

Emma Torres, the organization’s executive director and co-founder, said educating Hispanics about diabetes is the key to helping them fight it.

“Every Latino family that we know, there is somebody in their family with diabetes,” she said.

Although there are no statistics on the prevalence of the disease among Hispanics along the border, data from the Arizona Department of Health Services shows that 13.5 percent of Yuma County’s residents had diabetes as of 2010, the highest rate in Arizona. Hispanics represent nearly 60 percent of the county’s total population, according to 2010 Census data.

Diabetes has developed into a pandemic on both sides of the border from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Ocean during the past decade, according to Maria Teresa Cerqueira, the chief of the U.S.-Mexico Border Office of the Pan American Health Organization, part of the World Health Organization. She said the disease advances through poor eating habits and sedentary lifestyles that border residents inherit from their families and those around them.

“It’s a socially contagious disease,” Cerqueira said.

Ethnic disparities

Leandra Rosales, a Mexican immigrant residing in Somerton, said her diabetic father committed suicide in Mexico because he couldn’t stand the complications from the disease. Her mother died from diabetes complications. So did her mother’s mother.

Rosales, who was diagnosed with diabetes more than two decades ago, said for a long time she thought she was next in line to die. She said she didn’t know diabetes could be be managed until she started taking classes with Campesinos Sin Fronteras in 2000.

“It helped me a lot because I learned that you can control the disease, that you have to take care of yourself and you can live like a normal person,” Rosales said in Spanish.

Campesinos Sin Fronteras created a diabetes program in 1999 because there were no resources available for Hispanics with the disease in Yuma County’s border communities, Torres said.

“It was not something that was addressed for our population, and the services that were offered were only in English and were in Yuma,” she said. “And nothing was done here in this community.”

Many of those who sought assistance from Campesinos Sin Fronteras in the late 1990s didn’t know what diabetes was and believed they needed to stop eating completely when they were diagnosed with it, said Floribella Redondo, programs director for the nonprofit. Others would stop eating anything except lettuce and vegetables.

“A lot of them said, ‘Well, I went to a doctor and they told me I had diabetes but they didn’t tell me what diabetes was, so can you tell me what I have?’” Redondo said.

Hispanics on the border are twice as likely to get diabetes as whites, according to Cecilia Rosales, an associate professor of public health and director of Phoenix programs for the University of Arizona’s Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health.

“If you compare the border area to the rest of the state of Arizona, the problem definitely is much bigger along the border,” said Rosales, who has worked on border health issues for about two decades.

Although Hispanics are at higher risk for diabetes, Rosales said the influence of genes in the development of the disease is “very small,” adding that not everything about diabetes is known yet.

Children affected

Leandra Rosales’ son, Juan, was diagnosed with diabetes four years ago at age 15. For Juan, who was born in the U.S. and lives in Somerton, being diabetic means having to eat smaller portions and more vegetables, exercising regularly to control his weight and going to the doctor every three or four months to check the level of glucose in his blood. However, he said it had been nine months since his last doctor’s appointment.

“I was just lazy,” Juan said. “I am like, ‘I’ll make the appointment next week,’ and that week will pass and (I’ll say) ‘I’ll do it next week,’ and not do it.”

Redondo of Campesinos Sin Fronteras said the disease, which used to be called adult-onset diabetes, has developed among a growing number of Hispanic teens in the area during the past decade.

“Now we have some people that come to our programs that are 25, 26 years old, they have diabetes Type 2,” Redondo said, referring to the most common form of the disease. “We have had kids in this community that have been diagnosed with diabetes Type 2 and they are 9 years old.”

Diabetes put an end to Juan’s professional aspiration, becoming a Marine, when he was a junior in high school. He said he was told during a phone interview with the Marine Corps that he couldn’t serve because he was diabetic.

“I was confused. I was like, ‘What? Are you serious?’” Juan said. “I was kind of sad because it’s something I wanted to do and now I can’t do it.”

Will Humble, director of the Arizona Department of Health Services, said the increase in overweight and obese children due to poor nutrition and lack of exercise contributes to diabetes.

“Pediatric offices in Arizona, especially in the border area, now routinely have diabetes as a core part of their practice,” Humble said. “Now why is that? Well, it’s because this obesity epidemic has gotten out of control.”

The National Survey of Children’s Health conducted by federal agencies shows that 41 percent of Hispanic children ages 10 to 17 in Arizona were overweight or obese as of 2007, above the state average of 31 percent, while the rate for non-Hispanic white children was 22 percent.

“Now we’ve got this whole cadre of kids with Type 2 diabetes, and if they don’t get their weight under control and manage their diabetes properly they’re going to have a lifetime of medication and it’s going to end badly for them,” Humble said.

Rep. Lynne Pancrazi, D-Yuma, said promoting physical education in schools is key to preventing childhood obesity.

“If we do that, then we are overcoming future issues like diabetes or heart disease,” she said.

In 2008, Pancrazi was a primary sponsor of bills that would prohibit schools from eliminating or reducing physical education, among other programs, without governing board approval and to require school districts and charter schools to provide 150 minutes of physical education per week per pupil. Gov. Janet Napolitano vetoed the former, calling it unnecessary since governing boards already make such decisions, and the latter wasn’t heard in committee.

Pancrazi said such legislation would stand no chance of passing at present.

“It wouldn’t even be heard because our emphasis right now in the state Legislature is on test scores and on accountability for teachers and for students,” she said.

‘Healthy choice’

It has been easier for Somerton residents to take evening walks thanks to the three to four miles of sidewalks with lighting the city has built in recent years.

But these sidewalks don’t necessarily serve an aesthetic purpose. They are about getting the population to exercise, said Martín Porchas, Somerton’s mayor.

“The main focus is to connect all the pathways to the parks throughout the city,” he said.

Porchas said he believes between 35 to 40 percent of Somerton residents have diabetes. Ninety-six percent of the community’s residents are Hispanic, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Experts and advocates say a variety of factors on the border such as poverty, summer heat, unsafe neighborhoods, fear of law enforcement and a lack of options for exercise make it harder for Hispanics to eat healthy and be active.

“Some communities don’t have paved roads, they don’t have sidewalks, they don’t have lighting,” said Rosales of the University of Arizona. “When do people, especially in Arizona – when do we exercise because of the climate? It’s either early in the morning or late in the evening.”

Rosales and Cerqueira of the Pan American Health Organization said poverty on the border leads to poor nutrition among Hispanics, in part because many need to work several jobs to make ends meet and lack the time to cook healthy meals.

“They tend to buy more processed foods, fast foods and more calorie-dense like, you know, white bread and pasta than, say, fresh fruits and fresh vegetables,” Cerqueira said.

Zipatly Mendoza, office chief of the Arizona Health Disparities Center within the state health department, said some border communities lack places where people can exercise.

“It can be very rural areas, so it makes it more difficult to have access to a gym,” Mendoza said.

She said illegal immigrants in border communities may also stay home because they fear law enforcement and deportation.

“Is the healthy choice really a choice in some communities?” Mendoza said. “Some communities don’t have a healthy choice.”

The uninsured

Leandra Rosales, Juan’s mother, has heart problems and high blood pressure caused by diabetes but lost her coverage through the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System several years ago. Unable to work because of her health problems, she now goes across the border to San Luis Río Colorado, Sonora, monthly for the cheaper medical care available there.

“I have to get my medicine and I have to get my care,” Rosales said. “Where? Wherever possible.”

Between 18.5 percent and 25 percent of residents in U.S. border communities lacked health insurance from 2006 to 2008, according to a 2010 Pan American Journal of Public Health study drawing on census data.

The state health department doesn’t track the number of people crossing the border to seek medical care but acknowledges that it happens, said Pragathi Tummala, the department’s diabetes program manager.

Organizations such as Campesinos Sin Fronteras and community health centers in U.S. border communities offer education on diabetes and-or treatment for the disease for the uninsured.

The Regional Center for Border Health Inc., which has medical centers in Somerton and San Luis, provides treatment for diabetes and other conditions at discounted rates, said Amanda Aguirre, a former state lawmaker who is the organization’s president and CEO.

“We see anyone that needs health care,” Aguirre said.

She said her center developed a network of doctors and health centers on both sides of the border that provide care to the uninsured at a 65 percent discount. She said her organization’s medical centers take patients’ incomes into account when calculating the cost of care.

The Mexican consulate in Nogales offers weekly classes on nutrition and diabetes through a government program called Ventanilla de Salud – Window of Health in Spanish – that aims to promote healthy habits among Mexican immigrants and connect them with care.

“It’s important to educate the population because a lot of them don’t know the kind of danger they are in,” said Alicia Sander, a Mariposa Community Health Center health promoter who helps teach the classes.

State response

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention gives the Arizona Department of Health Services $250,000 a year to address diabetes. With it, the department maintains a coalition of over 300 organizations throughout the state and provides them with technical assistance, training and tips on effective community outreach, according to Tummala, the diabetes program manager.

The department received $1 million from the Legislature in 2006 and used the money in 2006 and 2007 for diabetes prevention, but the funding wasn’t renewed due to budget cuts, said Aguirre, who as a Democratic state representative persuaded lawmakers to include the money in the budget.

“One million for me was very little, but at least it was an attempt to get this moving,” Aguirre said. “One of the challenges was to make the Legislature understand why preventive services are effective and will save us in the long run more money.”

Suzanne Miller, regional director of program implementation and outreach for the American Diabetes Association and chairwoman of the Arizona Diabetes Coalition’s Advocacy Committee, said the Arizona State Legislature should require all health insurers doing business in Arizona to cover the costs of diabetes education. Many do already, but it isn’t mandated, she said.

“One of our long-term goals as the coalition is to ensure that people with diabetes have the opportunity to get diabetes education to help them manage their disease,” Miller said.

Humble said the state health department needs more resources to prevent obesity and diabetes but added that families have a responsibility to live healthier lifestyles.

“It takes a level of awareness not just with the public but with policymakers so that we get the resources that are necessary to make it happen,” Humble said. “But like I said, none of this is going to happen unless families take this seriously.”