Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Deteriorated properties prompt battles between struggling towns, professor

SUPERIOR – The unmistakable sound of giggling children draws the attention of real estate developer Bill Holmquist as he walks along Main Street in this copper mining town.

The children are playing in the backyard and on the steps of a vacant structure that was once an office building.

“It’s haunted,” they yell.

A recent coat of purple paint covers the front of the building, but the view from the side and back tells a different story: Some windows are broken and covered with plywood and the yard is strewn with weeds.

Holmquist shoos the children away, warning that something could fall of them.

“At some point somebody’s going to get hurt,” Holmquist said.

The building is one of seven commercial properties in the half-mile-long business stretch of Main Street belonging to Glenn A. Wilt, a professor emeritus specializing in finance and real estate at Arizona State University’s W.P. Carey School of Business.

Since 1991, Wilt has purchased at least 41 properties in Superior, including commercial and residential buildings and vacant land, according to Pinal County Assessor’s Office.

Other commercial buildings along Main Street include the former homes of Iberri Market, BBB Grocery Store, Sprouse Reitz Co. and the Apache Leap bar. All are boarded up, as are the former homes of the Knights of Columbus, a Baptist church and Los Reyes Club, some of the other buildings Wilt owns around town.

Former Superior Mayor Michael Hing said many of Wilt’s buildings have deteriorated over time, some to the point of collapse.

“His buildings are really dilapidated,” Hing said.

Further east in Globe, where Wilt owns at least 18 properties, the city enacted a blight code after a jury found him liable for a 2005 fire that claimed a historic hotel he owned in the downtown area.

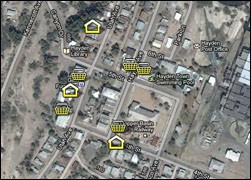

In the town of Hayden, where Wilt owns most of the commercial buildings downtown, the mayor says his unoccupied and neglected structures stand in the way of community’s hopes of revitalizing the area.

A Cronkite News Service review of county assessors’ records found that Wilt owns at least 97 properties in Pinal, Gila and Maricopa counties.

Twenty-four are rental houses and apartments in the Phoenix area – mostly in Tempe – and the rest are in Globe, Miami, Superior and Hayden, rural communities that have struggled since the decline of copper mining.

His portfolio includes homes, retail stores, drug stores, old hotels, schools, churches, empty pieces of land and even a funeral home.

Officials in Superior and Globe have tangled with Wilt dozens of times through the years over the condition of his properties, citing him, among other things, for fire code violations, endangering the public, letting weeds grow and vermin infestation.

Officials in the towns say Wilt’s buildings stand in the way of efforts to make their downtowns more attractive to businesses, tourists and potential residents.

“His dream has turned into our nightmare,” Hing said.

The professor

When Wilt started buying property in the Superior, Hing said, residents perceived him as a real estate expert looking to help revive the town.

“Buildings were actually sold to him knowing that Dr. Wilt was a wealthy man, had a great vision for Superior,” he said.

In a 1996 interview with the Superior Sun, a weekly newspaper, Wilt described the town as “a San Francisco-looking place” and said he envisioned it becoming a bustling art and tourist mecca with a theme of copper and Hispanic culture.

“Plays on that theme will make the town grow,” he was quoted as saying.

But Hing and other officials say their dealings have mostly involved battles over the condition of Wilt’s properties. Despite the back and forth, as well as coverage by local news outlets and Phoenix-area sources such as the East Valley Tribune and KPHO-TV, they say they haven’t been able to fathom what Wilt intends to do with the properties.

Fernando Shipley, Globe’s mayor, said Wilt is pleasant and made promises believably in the few times they have met but is a bully when city officials make demands.

“He’s got resources, and so his attitude has always been, ‘Take me to court. I’m smarter than you and I have more money than you,’” he said.

Wilt has taught at the W.P. Carey School of Business since 1963.

His biography on the school’s website as of early December described him as “a loved and respected professor who has taught courses on the fundamentals of finance, real estate finance, security analysis and portfolio management.”

Wilt manages his properties through different real estate companies he owns. They include Superior Development Co., Collegetown Development Co., Globe Development Co., Hayden Development Co. and Miami Development Co., according to records maintained by the Arizona Corporation Commission and Secretary of State’s Office.

Debbie Freeman, spokeswoman for the W.P. Carey School of Business, said Wilt last taught at the school in spring 2011 and won’t be teaching any more classes because he is retired. He had taught a course in Financial Markets and Institutions once a semester since 1997, according to the school’s website.

Thomas Bates, Wilt’s chair in the school’s Department of Finance, said in an email that he wasn’t privy to Wilt’s work beyond ASU. He declined to comment on his work at the school.

Court documents identify Wilt as 77 and unmarried. Public records don’t show whether he has children or heirs.

Cronkite News Service made repeated, unsuccessful attempts to interview Wilt over three months, leaving telephone messages at his business and ASU office numbers as well as on his cellphone and sending letters by regular and certified mail.

Jean-Jacques Cabou of Phoenix, listed as Wilt’s attorney in a civil case pending in Maricopa County Superior Court, said Wilt wouldn’t talk with Cronkite News Service.

Superior

“No Trespassing” spray-painted in red is a common sight in this town. Business and the population dwindled after copper mining declined two decades ago.

Wilt purchased many Superior properties at what Hing called cheap prices. Records show he paid $35,000 for the Sprouse Reitz Co. building, $22,500 for the Knights of Columbus building and $6,000 for a former garage, for example.

In a 1998 letter to the Superior town administration, Wilt described plans to develop some of his properties such as applying for a grant from the Arizona Historic Preservation Office to restore the Uptown Theater, a Main Street landmark he purchased in 1995. He also said he planned to set up an outdoor marketplace at the former Apache Leap bar. Neither happened.

Town records show that the fire department has given Wilt 43 orders since 2007 to clean up his properties. The violations included dilapidated structures, hazardous buildings, weeds, litter and junk vehicles.

The town has gone to Superior Magistrate Court 44 times since 1997 over the condition of his buildings, records show.

Perhaps his most contentious dealings with the town involved the Uptown Theater, built in 1923 and not in use when Wilt purchased it.

After large sections of the roof collapsed in 1998, the town declared the building dangerous and a Pinal County Superior Court judge ordered Wilt to demolish parts of the theater to prevent it from damaging adjoining buildings. In a letter to the town, Wilt promised to renovate it.

By 2008, according to fire department documents, more than half of the roof had collapsed and an adobe portion of the building had partially fallen onto a commercial building that Holmquist, the real estate developer, was renovating.

Holmquist sued Wilt and the town, claiming authorities hadn’t done enough to prevent it. He and Wilt later agreed to settle before a mediator. Terms of their agreement were kept private.

Wilt asked for more time to come up with a plan to save the theater, but town leaders rejected his request. He later turned the building over to the city, which spent $49,000 to demolish it in August 2009.

Superior Police Chief Lou Digirolamo said the town had tried for a long time to get Wilt to voluntarily fix his properties and resolve problems such as weeds, broken windows, vermin and junk vehicles.

“It’s been a slower process than we anticipated,” he said. “These things take time.”

In November, the town came to agreement with Wilt to resolve code-compliance issues. According to settlement document, Wilt agreed to a schedule ranging from 30 to 180 days to fix his properties.

For instance, Wilt agreed to a 90-day time frame to file for a building permit to fix part of the former Iberri Market and to stabilize the roof of the Sprouse Reitz building. Within 30 days, he pledged to remove pigeon waste and repair the roof of the former Knights of Columbus building.

In the agreement, Wilt complained that the town unfairly singled him out, and town authorities agreed to deal with him and other violators equally.

As of mid-December, Wilt had complied with four of the five projects with 30-day deadlines, Digirolamo said.

While Wilt’s vacant structures remained unoccupied as of mid-December, Digirolamo said he’s hopeful that the agreement will help revitalize the community.

“I envision a day that every building on Main Street is occupied with business and anybody can go up and down Main Street,” he said.

Globe

Wilt’s properties in Globe were in compliance with the city’s building and fire codes as of December, but officials said the agreement that made that happen earlier in 2011 followed years of wrangling and a fire that claimed a downtown landmark.

Early on July 17, 2005, fire destroyed the historic Pioneer Hotel, which was home to a coffee shop and art gallery on the first of its four floors but otherwise vacant. Wilt bought the building in 2003, according to records maintained by the Gila County Assessor’s Office.

The adjacent Hollis Theater, under separate ownership, also was damaged. The city’s fire chief said the fire most likely was started by vandals because the building wasn’t secured.

Artist Frank Balaam, who rented space from the coffee shop for his gallery, said he lost nearly 1,000 paintings from about 25 years of his work. He sued in Gila County Superior Court, contending the fire was a result of Wilt’s negligence.

“It’s just awful,” Balaam said. “You spend your life in creativity and then to be at the mercy of someone who spends their life in destruction.”

In December 2009, a jury ruled in Balaam’s favor and ordered Wilt to pay him $223,000 in damages, court records show.

Christopher Collopy, Globe’s building inspector, said that after the Pioneer Fire the city got more rigorous in its efforts to make Wilt accountable for his buildings.

Wilt owns at least 18 properties in Globe, including: the 1910 Elks building, home to an antique store on one of its three floors; the former Hill Street School, which has a skating rink that Wilt lets the community use; and the East Globe School, which is partially leased for a day care center.

Cronkite News Service was unable to determine whether any of Wilt’s other Globe properties were occupied, but his residential properties had “For Rent” signs with his business phone number listed. Records show he also owns a former lodge and a store in neighboring Miami, where officials didn’t return messages about the properties.

Collopy, who has dealt with Wilt for about nine years, said the problem has always been the condition of Wilt’s properties.

In nine citations recorded in Globe Magistrate Court since 2009, the city accused Wilt of failing to rid his properties of combustible materials, broken windows and vermin and not addressing dilapidation. The city claimed that three of Wilt’s buildings were fire and electrical hazards.

Mayor Shipley said Globe enacted an anti-blight code and formed an enforcement committee to deal with Wilt and other violators, but he said Wilt postponed attempts by the fire marshal to inspect his buildings.

When officials got into the East Globe School for an inspection, they found it stuffed with old carpets, couches and other items that blocked the fire exits, Shipley said.

“We finally cornered him and then we got into the building and then it scared us,” he said.

Collopy said the East Globe School looked like a “collection from numerous yard sales.”

“You can start from taxidermy animals and go all the way up to grandfather clocks and antiques to plain junk, old carpets,” he said.

A city inspection of the Hill Street School found that a collapsed ceiling had severed a fire sprinkler line. In a memo, Collopy warned city leaders that the rest of the ceiling could fall and “cause serious injuries” to those using the the skating rink.

The city then went after every violator in the area, including Wilt, but after multiple attempts to get him to comply failed, Globe sued him in 2009 in local courts, Shipley said.

“Once he saw how serious we were, he started cooperating, but it took a major show of force,” said Kane Graves, Globe’s attorney and city manager. “It’s just a mystery to us what he’s doing spending all this money and just letting it rot.”

Earlier this year, all nine cases were dismissed after Wilt agreed to fix his properties and deposit refundable bonds of $3,000 to $6,000 for each. If he didn’t fix them, the city would use the money to do so.

Collopy said all Wilt’s buildings were in compliance with the minimum standards by October 2011.

“He seems to be making some improvements on his buildings and hopefully he continues in this manner,” he said.

Hayden

The business district in this tiny town 95 miles southeast of Phoenix is largely abandoned. Most of the commercial buildings – at least 15 of them – are Wilt’s, according to records maintained by the Gila County Assessor’s Office.

The police station is the only open facility on Hayden Avenue, what used to the town’s main business street. Next door, the former home of Hayden United Methodist Church, with peeling paint, cracked walls and a broken front window, bears a “Building for rent” sign from Hayden Development Co., owned by Wilt.

A furniture store occupies one of Wilt’s properties, but the others showed no sign of use. Two, a Roman Catholic church and an apartment building, had burned and were in disrepair.

“He has me very angry right now because he has no regard for our town and what we have to deal with on a daily basis with his buildings,” Mayor Monica Badillo said. “It’s hurting our image.”

The town doesn’t have a grocery store, and residents have to travel 10 miles to the nearest one in Kearny or shop at a convenience store. But Badillo said all the buildings that could be used for a grocery store are in Wilt’s possession.

Over the years, several people have inquired about renting the buildings and opening businesses, Badillo said, but she said Wilt won’t agree.

Once, she said, he asked her to find anyone wanting to rent a former drugstore to open a business and he would charge them a small fee that would increase that as the business grew. However, she said, Wilt changed his mind after she found a candidate.

Badillo said a building belonging to Wilt across from her house is infested with bats that come out in droves in the evenings, but she said he’s not responded to her complaints.

She said that the town has invited Wilt to discuss the state of his properties, but he’s only come a few times.

“The only time he shows up is when he wants something,” she said.

Most recently, about six months ago, he came to town asking for permission to open up one of his buildings as a medical marijuana dispensary, she said. Officials declined, Badillo said.

Angella Ramirez, director of the Copper Basin Chamber of Commerce, which covers Hayden, Kearny and Winkleman, said the condition of Wilt’s buildings discourages businesses from coming to a town that should be attractive to investors.

“If I was a potential investor, I would probably think twice,” she said. “It makes the town look like a ghost town.”

Energized by other towns’ success in dealing with Wilt, Badillo said Hayden officials plan their own legal offensive.

“I really tried the approach of being nice in the beginning, and everything he told me, he went back on his word,” she said. “So nice is out the window.”