Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Arizona joins national effort to help homeless veterans

PHOENIX – To Army veteran Robert Herr, this downtown Starbucks is just another place to grab a cup of coffee on his days off from work.

But just more than a year ago, when he was homeless and living in his car in California, Starbucks was the place Herr went for shelter, drinking free refills and eating the occasional free snack.

“My main survival was pretty much Starbucks during the day and then finding a good hiding place at night,” he said.

When Herr’s father died in late 2010, he came to Phoenix to be close to his 8-year-old son. He ditched his car and slept in bushes outside the Carl T. Hayden VA Medical Center until a VA liaison connected him with U.S. Vets, a private organization that provides temporary housing, counseling and job placement for veterans.

“I wouldn’t wish it on anyone,” he said of his experience.

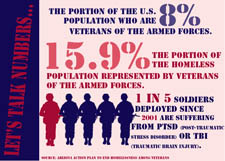

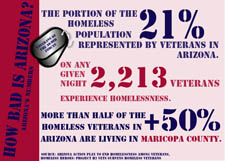

Arizona has a higher number of homeless veterans than most other states, in part because of the draw of its mild winters. More than 2,200 veterans are homeless in Arizona on any given night, making up one of every five people on the street, according to estimates from the state Department of Veterans Services.

Alarmed by the scale of the problem and the lack of resources available, state and private organizations are joining a national effort to make help available to those on the street.

“At some point in time, that individual put on a uniform and gave their formative years of life to the country,” Brad Bridwell, former homeless veterans services coordinator for the Arizona Department of Veterans Services. “Anyone who puts that uniform on should expect that in their time of need we come forth for them when they’re struggling back at home.”

Factors

Veterans are less likely to fall into poverty, but when they do they are more vulnerable to homelessness, in part because they often lack family support, according to a report by the VA and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The 2010 American Community Survey showed that about 7.4 percent of Arizona’s veterans had been in poverty in the previous year. That means nearly 40,000 of the state’s more than 500,000 veterans were at a greater risk of experiencing homelessness.

But experts say there’s no definitive explanation for why veterans are at greater risk of becoming homeless.

“I don’t think it’s any one reason,” said Mike Simpson, men’s shelter director at Crossroads Mission in Yuma. “It’s a combination of many factors.”

Simpson said veterans who battle homelessness also may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental and physical illnesses, and they begin to mask those issues with drugs or alcohol.

“That’s a recipe for a disaster,” he said.

Veterans may have limited job skills and experience when they leave the service. Military training doesn’t always apply to civilian jobs.

Herr said he had several jobs during his six-year stint in Germany 35 years ago, including repairing tanks and serving with the unit police. He said neither of those jobs helped him get work outside the Army.

“When I got out of the military, the challenge was not having a defined career,” said Herr, who now lives in temporary housing provided by U.S. Vets and works for a microchip company.

Jonnie Arnold, a clinical supervisor at U.S. Vets, said those who serve often get very specific training, like repairing helicopters.

“Most of the skills they were learning were for war, so they come back and they have no transferable job skills,” she said.

It’s also difficult for veterans to transfer back into civilian life because they’re used to simply following orders.

That was true for Bradwin Lauriault, who served as an Army tactical communications chief in Italy and in the U.S. during his stint from 1970 to 1976. When he left the military, he didn’t know where to go or what to do after being part of a troop for so long.

“I wasn’t prepared to be put out of the service,” said Lauriault, a veterans service manager at the same U.S. Vets location that helped him escape homelessness.

Many veterans may have already been at a higher risk for homelessness when they joined the military.

John Kuhn, national director of VA Homeless Prevention Services, said the military was unpopular after the Vietnam War ended, and the pay wasn’t very high. So the military began taking recruits who were less educated and who may have lost touch with family members, both risk factors for homelessness.

“Veteran status can be a catch-all for other social factors going on during the period with those veterans entered the service,” he said.

Arizona’s budget cuts contribute to the problem here, said Bridwell, who now is community development director with Cloudbreak, a private company that developed temporary housing for U.S. Vets.

Bridwell said single veterans who didn’t serve long enough to get VA medical benefits are likely unable to access Medicaid in the state after recent cuts to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System.

“This state has been hit a little bit harder than most,” he said.

Regardless of the reasons a veteran falls into homelessness, it’s often difficult for him or her to get out. Lauriault said veterans experiencing homelessness are often unaware or skeptical of the help that is available, so they remain in “survival mode.”

“They have to realize that they have to be self-reliant and ask for help,” he said. “They have to set aside a sense of pride.”

Iraq/Afghanistan veterans

The Phoenix VA Health Care System joined the state Department of Veterans Services, the Arizona Coalition to End Homelessness, the city of Phoenix and nonprofit organizations in scanning area streets for homeless veterans in November, part of a project called H3 Vets. Their goal was finding as many homeless veterans as possible and connecting those in the worst situations with immediate help.

Among other things, the survey showed that the percentage of veterans on the street who served in Iraq or Afghanistan had more than doubled in a year.

Veterans of the current wars are facing homelessness more quickly than their predecessors. Sean Price, the homeless veterans services coordinator for the Arizona Department of Veterans Services, said Vietnam veterans fell into homelessness an average of six years after they left the service, but many veterans of recent wars are becoming homeless in two years or less.

The economy plays a large role in that. Michael Leon, homeless veterans coordinator for the Phoenix VA Health Care System, said veterans from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are coming home to a tough job market.

“We’re getting more displaced vets now,” he said.

Marcy Karin, an associate clinical professor at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law who has written several articles on the issues veterans face, said a lack of family connections is likely worse for veterans of the current wars.

“When you look at the stress that service places on your families, if you’re married if you have kids, it’s not surprising that some of the systems are breaking down,” she said.

Price said the VA and the state are keeping an eye on veterans who are most at risk for homelessness when they get out of the service. They aim to prevent homelessness in this generation by using services like the Military Family Relief Fund, which helps veterans and their families get through financial struggles.

“You see Vietnam and post-Vietnam vets that are living on the streets,” Price said. “We don’t want that again.”

Women veterans

Norma Thomas drove motorcades and managed commissaries on U.S. Navy bases in Naples, Italy, and Philadelphia during her six-year service in the early 1980s. She said when she left, she struggled to find jobs with good salaries.

“Just because you had that training in the military, it’s no easier to get a job on the outside,” she said.

She moved from Colorado to Phoenix so her two sons could be close to her parents. She cared for her mom and dad until they passed away within two years of each other, and she said losing them helped send her into a deep depression.

“I thought that I could beat depression,” she said. “It just got to the bottom where it was too much.”

After spending time in the VA hospital and in a shelter, she was connected with a VA liaison who helped her get into U.S. Vets, where she has temporary housing and help finding a job.

“I’m not staying down,” she said. “I have to pick myself back up.”

Women veterans like Thomas are twice as likely to experience homelessness than male veterans and non-veteran women, according to the VA and HUD report.

Karin, the ASU law professor, said as more women see battle in Iraq and Afghanistan they experience post-traumatic stress disorder, which may lead them to pull away from family and friends. She said women are also less likely to seek help at the VA because they view it as “a male institution.”

“I think the VA is doing a lot to change that perception, but it still exists,” said Karin, also a director at the college’s Civil Justice Clinic.

Thomas said she knew she could receive treatment at the VA hospital, but she knows many women who don’t know what benefits they qualify to receive.

While male veterans without homes often live on the streets, homeless female veterans tend to stay with family members and friends, which makes them difficult to find and to help. Many of them won’t seek help until they run out of places to stay, said Joan Sisco, a Marine veteran and president of Veterans First Ltd.

Sisco said there aren’t enough housing options specifically for women in Arizona, so she worked with the Community Housing Partnership to develop a unit of affordable apartments for women veterans called Mary Ellen’s Place. She said it’s crucial for women to be around others who share the same perspective on being a veteran.

“It’s a proven fact that women veterans do better with other women veterans who understand what they’re going through,” she said.

Sisco said women need to be treated differently for illnesses and trauma, and the VA has started to focus treatment programs to address the unique needs of women. Still, she said the organization has a ways to go.

Thomas said she wants other female veterans to know that they are just as entitled to help as men are.

“If you can put your name on the line, you should be able to be treated the same as guys,” she said.

Solutions

The VA has set a goal of ending homelessness among veterans by the end of 2014. Its plan, announced in 2009, focuses on getting chronically homeless veterans off the street and preventing veterans from falling into homelessness.

To reach that goal, the VA provides housing vouchers with the Department of Housing and Urban Development to veterans who are chronically homeless and need long-term help. The agency also funds a grant that reimburses organizations for each day veterans use their shelters or temporary housing. One new program, Supportive Services for Veteran Families, awards grants to organizations to keep veterans with families off the streets.

Kuhn said having “an alphabet soup” of programs is important because no two veterans need the same type or amount of help.

“Veterans are not a homogeneous population,” he said.

The Arizona Department of Veterans Services is helping organizations in the state get as many of those VA grants as possible. Price said Arizona has traditionally been lacking in beds and services for homeless veterans, but that’s going to change.

“We’re going to get as many strong applicants as possible to get those special grants because we have to build the capacity here,” Price said.

Price, Bridwell and others developed a state plan to localize the VA’s plan to end homelessness. Price said the objective right now is reaching veterans who have been homeless the longest because they are the most at risk for dying on the streets. He said chronically homeless veterans are a small group that uses up the majority of the resources available, so it’s imperative to get them into programs that provide long-term care.

“These are people that have mental illnesses, and they have disabilities,” he said. “They’ll never be able to function or support themselves, so they need that program.”

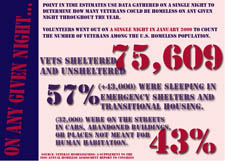

Bridwell said the number of shelter and transitional beds in Maricopa County available to homeless veterans has increased from about 170 to more than 1,000 since 2008.

“We’re making incredible strides,” Bridwell said.

Kuhn said the Obama administration’s support has, so far, ensured that under the direction of the Veterans Affairs secretary, the VA is getting the money it needs to carry out the national plan to end homelessness.

“The tipping point was the secretary and the current administration,” he said. “They came into office and said it’s simply unacceptable that we have homeless veterans,” he said.

Moving forward

The resources available to veterans are increasing and improving. Now organizations have to make sure veterans on the streets know about them.

Arnold, of U.S. Vets, said even though some veterans shy away from services, it’s important for them to know they can get help when they’re ready.

“We should be be going under the bridges, to the shelters, on the streets,” she said.

Kuhn said the key to success at the state and national level is making sure veterans get the right amount of services and money, no more and no less.

“We have to do it right,” he said. “We have to spend this money effectively and efficiently.”

For Herr, who once survived at Starbucks, the challenge now is preparing to leave U.S. Vets and be back out on his own. He’ll soon have to find a permanent place to live.

He said he’s not a success story yet, but he is motivated to support himself and his son.

“He’s probably the only thing that keeps me going, besides my spirituality,” he said.