Cronkite News has moved to a new home at cronkitenews.azpbs.org. Use this site to search archives from 2011 to May 2015. You can search the new site for current stories.

Medicaid squeeze could squeeze some rural hospitals to death

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story incorrectly attributed ownership of two facilities to Page Hospital. In fact, the Page Rural Substance Abuse Transitional Facility was owned by Encompass Health Services and a rural stabilization and recovery unit in Holbrook is owned by Community Bridges Inc.

WASHINGTON – For years, Holy Cross Hospital managed to keep the doors open to the only nursing home in Nogales, despite losing up to a reported $100,000 per month on its 26 residents, all of whom rely on Medicaid for health insurance.

But in the wake of deep cuts to the Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System – the state’s Medicaid program – Holy Cross said it will shut down the decades-old nursing home on Feb. 3.

“A Medicaid-only (facility) is not financially sustainable,” Debbie Knapheide, Holy Cross’ site administrator, said in a statement. Because AHCCCS only pays a fraction of a Medicaid patient’s medical bills, the hospital is left to absorb the remaining costs.

“We now recognize that continuing this program could pose a risk to the future viability of our hospital,” she said in a separate letter to Nogales and Santa Cruz County residents.

Across the state, rural hospitals like Holy Cross are facing “significant and irreversible harm,” as the Medicaid-dependent facilities see already thin margins squeezed by AHCCCS cuts to reimbursement rates and by swelling numbers of Medicaid and uninsured patients.

“The cuts are going to disproportionately affect rural hospitals over urban hospitals,” said Lynda Bergsma, director of the Arizona State Office of Rural Health at the University of Arizona. “It’s basically a rule of thumb (that) the rural population is older, sicker and poorer.”

In 2011, six of 14 state-designated “critical access hospitals” in Arizona – rural hospitals in isolated medical service areas – operated at deficits, and four of them are at risk of closure, according to hospital administrators.

Those officials now fear that the number of troubled hospitals could climb to as many as nine after the state cut reimbursement rates – twice so far in 2011 – and imposed new restrictions on AHCCCS enrollment, which is expected to force about 100,000 Arizonans off the rolls this year.

“You can only crash a system down so far before you’ve imploded it entirely,” said Jim Dickson, CEO of Copper Queen Community Hospital in Bisbee. “There’s coming a tipping point. It keeps me up at night.”

A system out of balance

Losing money is a fact of the health care business. Uninsured patients typically can’t pay their medical bills and Medicaid patients pay less than it costs to actually treat them.

But most hospitals manage to make up the difference each year, primarily through a practice known as “cost shifting” – also known to hospital officials as the “hidden tax” on health care.

Under cost shifting, hospitals raise their prices, which lets them earn more from privately insured patients. That offsets the losses they incur from Medicaid patients, because AHCCCS pays a set fee for treatment, regardless of price.

Because urban hospitals generally treat a higher proportion of privately insured patients than rural hospitals, more of their patients are able to pay the increased fees. That can allow urban facilities to achieve substantial profit margins.

But in rural hospitals, where poverty and unemployment rates tend to be greater, the payer mix consists of a higher proportion of Medicaid patients. That makes cost-shifting less effective by restricting the number of patients from whom the facilities can earn profits – necessary to replace old or broken equipment, pay employees competitive salaries and ensure quality of care year after year.

“Rural hospitals are higher cost by the nature of their business,” Dickson said.

In the past decade, the state has tried to help by establishing multimillion-dollar funding pools that provide assistance to the state’s rural hospitals.

Little Colorado Medical Center in Winslow has received about $1 million in such assistance each year since 2006, “which actually give(s) me a chance to have a black rather than a red bottom line,” said Jeff Hamblen, the hospital’s CEO.

But the impact of those types of assistance to hospitals has dimmed since December 2007 and the official start of the recession.

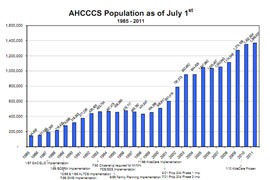

Since then, enrollment in AHCCCS has climbed 20 percent to a record-high 1.3 million Arizonans. As a result, hospitals have had to treat an increasing number of patients unable to pay their full medical bills, digging into what margins the hospitals had been able to achieve.

As the state footed the bill for the one in five Arizonans on Medicaid, the AHCCCS budget ballooned from $5.7 billion in 2008 to $7.6 billion in 2011. With the state facing a fiscal 2012 budget shortfall of $1.2 billion, the legislature cut AHCCCS funding by more than 20 percent earlier this year.

In a January 2011 letter to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), Gov. Jan Brewer said there was “no other viable alternative” to the cutbacks, noting that nearly $1 billion of the state’s $1.2 billion shortfall was attributable to the growth in AHCCCS spending.

“This explosive Medicaid growth threatens to consume the core functions of state government,” she wrote. “We cannot maintain a Medicaid program at the expense of public safety and our children’s education.”

A spokeswoman for AHCCCS said the state is sensitive to the “unique set of circumstances” faced by rural hospitals but that there is only so much the government can do.

“We do have budget issues and we do need to address those,” said Monica Coury, the spokeswoman. “We are not trying to force closures and that sort of thing.

“The bottom line for us is we try to make ourselves accessible so if there are systems out there who really are struggling, we are very open to having them come in and talk to us so we can see what’s going on,” she said.

But in an August letter to Brewer, Dickson said the cuts “will have a devastating impact on these rural hospitals and the communities that they serve.”

Among other changes – expected to save the state up to $500 million – AHCCCS in July froze enrollment for childless adults, effectively dropping about 100,000 people from the program. A lawsuit challenging that cut has been unsuccessful, with an Arizona Court of Appeals panel on Dec. 6 upholding the state’s right to implement the enrollment freeze and confirming its authority to repeal Prop 204 – the voter-approved measure that afforded childless adults coverage under Medicaid.

AHCCCS also cut the rates it pays medical providers, by 5 percent in April and another 5 percent in October. The second cut was given a formal OK by the federal government on Nov. 22.

With AHCCCS rolls at an all-time high, hospitals are seeing more Medicaid patients than ever; at the same time, the cuts to reimbursement rates forces the facilities to absorb even greater losses for doing so.

“Many of these (rural) hospitals are running very close to the edge,” Bergsma said. “If they lose a million dollars a year, you can imagine what that’s going to do to them.”

Administrators estimate that the two rate cuts will cost rural hospitals at least $9 million in income this fiscal year. The impact of the enrollment freeze could top $50 million, as those 100,000 childless adults lose AHCCCS coverage and likely become uninsured and unable to pay for care at all, leaving hospitals holding the entire bill for their care, Hamblen said.

“If you’re on the AHCCCS program because you don’t have health insurance (and) now you’re kicked off, what category do you think you’ll end up in?” he asked. “They’re only on AHCCCS because they didn’t have anything else.”

When the cuts hit home

In 2010 – before the AHCCCS cuts – Holy Cross Hospital operated at nearly 20 percent deficit and lost more than $4 million, despite being part of a large hospital system and receiving at least $771,000 in state assistance. Five other rural hospitals are also operating at deficits, according to hospital administrators.

To keep their doors open, they have few options.

With little room to cost-shift any more than they already have, multiple hospital administrators said rural facilities may have to cut services, like the Holy Cross nursing home in Nogales. With their thin margins, service cuts mean staff cuts, said Peter Wertheim, a spokesman for the Arizona Hospital and Healthcare Association.

Copper Queen Community Hospital eliminated obstetrics services and cut 10 staff members, leaving Bisbee-area pregnant women to travel farther for labor and delivery.

“What are you going to do if you’re paying out more than you’re taking in?” asked Little Colorado’s Hamblen. “You’re going to have to reduce what you’re paying. In a health care institution, that means staff cuts.”

But layoffs impact the quality of care a hospital can provide because health care is a “high-touch industry” that relies on nurses, doctors and lab technicians, among others, to keep a hospital running effectively, Hamblen said.

“If you start whacking staff then you’re not a high-touch industry anymore,” he said. “There’s a point where you just can’t do it.”

While Little Colorado has been forced to nix plans for the expansion of an intensive care unit, it remains one of the healthier rural hospitals in the state and has thus far avoided service cuts. Others have not been so lucky.

In addition to the looming closure of Holy Cross’ nursing home, for example, La Paz Regional Hospital may be forced to close two rural health clinics and an urgent care facility, according to a letter from Dickson to CMS.

Dickson said he expects that a rural hospital in the state will close if nothing is done to stem further losses. While a closure would leave an entire community without accessible health care, it would also deprive the community of more, Bergsma said.

“In rural communities, hospitals are often one of the largest employers,” she said. “The hospital is the economic driver of the community.

“If that hospital closes, then that community is going to substantially reduce,” she said. “People are going to leave and not a whole lot of new people are going to come, so that community is going to suffer.”

Hospital administrators are looking at other options that might help them hold off cuts and closures. Coury said multiple hospitals have met with AHCCCS to explore possible solutions.

“We want to be able work with people, and that does come down to working with facilities one on one,” she said.

In Dickson’s letter to CMS, he proposed that rural hospitals be permitted to finance a funding pool that could draw federal dollars to support the rural hospitals, at no cost to the state. Unless the proposal is approved, however, Dickson said rural hospitals will have no alternative means to help them stay afloat.

Currently, federal funds can only be drawn down from units of government.

Coury said AHCCCS has seen the funding pool proposal and passed it on to CMS. The federal agency has not yet issued a decision on the request.

“If something isn’t done soon,” Dickson said, “at least two or three of the hospitals below the I-10 corridor, on the border, located valleys and mountains away from each other, will close.”